FOR THURSDAY, READ THURBER CH. 3 AND THE FREEMAN EXCERPTS ON SAKAI.

First assignment by Thu.

"All of American history comes from the Civil War. It is the most important event in our history. Everything before it led up to it, everything since, everything, is a consequence of it." -- Ken Burns

From Article I, section 2

Akhil Amar on the Three-Fifths Clause:

The radical vice of Article I as drafted and ratified was that it gave slaveholding regions extra clout in every election as far as the eye could see - a political gift that kept giving. And growing. Unconstrained by any explicit intrastate equality norm in Article I, and emboldened by the federal [3/5] ratio, many slave states in the antebellum era skewed their congressional-district maps in favor of slaveholding regions within the state. Thus the House not only leaned south, but also within coastal slave states bent east, toward tidewater plantations that grabbed more than their fair share of seats. ... The very foundation of the Constitution’s first branch was tilted and rotten.

And not just the first branch. The Article II electoral college sat atop the Article I base: The electors who picked the president would be apportioned according to the number of seats a state had in the House and Senate. In turn, presidents would nominate cabinet heads, Supreme Court justices, and other Article III judges.Consequences of the Three-Fifths Clause. From William Lee Miller, Arguing About Slavery:

Five of the first seven presidents were slaveholders [Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson], for thirty-two of the nation’s first thirty-six years forty of its first forty-eight, fifty of its first sixty four, the nation’s president was a slaveholder. The powerful office of Speaker of the House was held by a slaveholder for twenty-eight of the nation’s first thirty-five years. The president pro tem of the Senate was virtually always a slaveholder. The majority of the cabinet members and — very important — of justices of the Supreme Court were slaveholders. The slaveholding Chief Justice Roger Taney, appointed by slaveholding President Andrew Jackson to succeed the slaveholding John Marshall, would serve all the way through the decades before the war into the years of the Civil War itself; it would be a radical change of the kind slaveholders feared when in 1863, President Lincoln would appoint the anti-slavery politician Salmon P. Chase of Ohio to succeed Taney.

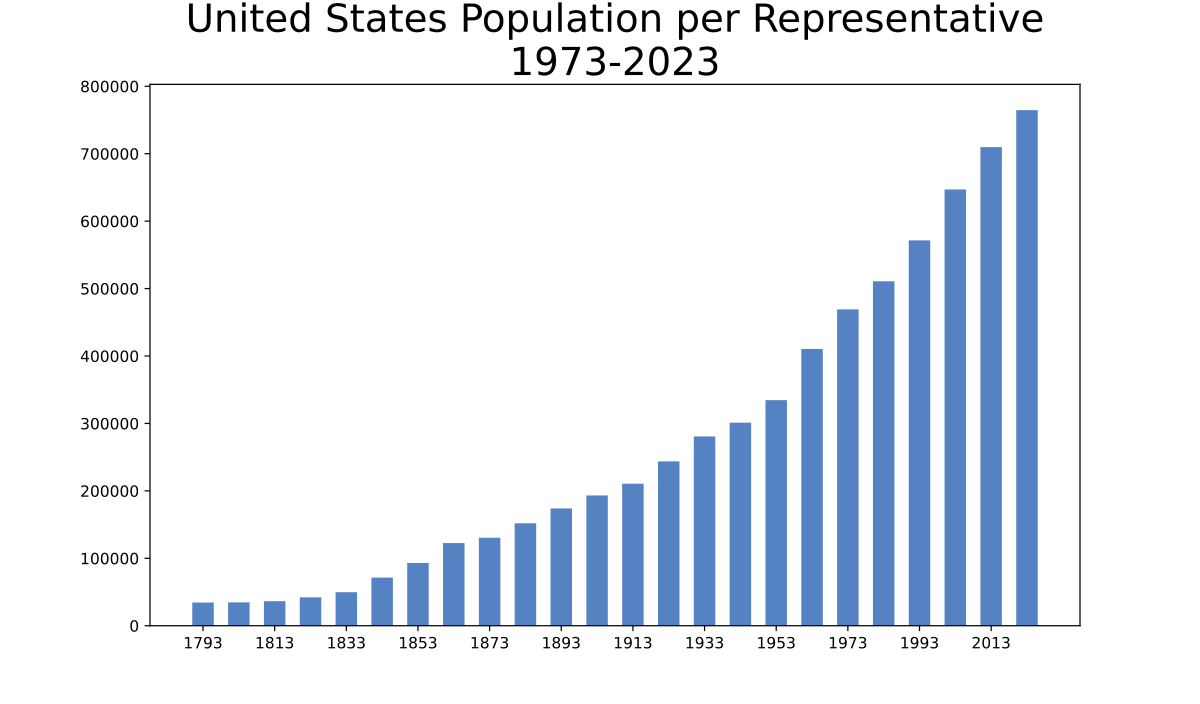

The size of Congress (Davidson 28-29)

, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link

The relevant constitutional provision is Article 4, section 3:

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the CongressThat’s right. All it takes to create a new state is the passage of a federal law. Right now, assuming they were willing to use the nuclear option to abolish the filibuster for state admissions, any unified government could make Puerto Rico or DC a state, or (with the consent of the state leg) divide Texas (or Wyoming) into any number of states. WIth just a law. Irreversibly. And the constitution puts no population or land size constraints on the process either.

These three features of the statehood process—irreversibility, a low threshold for creation, and no population/size constraints on the creation of a state—made the statehood process incredibly destabilzing in the 19th century. Any majority, at any time, could rearrange the balance of power in the legislature and the electoral college. And it unambiguously exacerbated the slave crisis: so many of the major flashpoints over slavery between 1820 and 1860 involved the flawed statehood process: the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the Lecompton Constitution fight, even the Dred Scott decision.

"Institutionalization" (Davidson, pp. 26-27)

- "Well-bounded": Membership and leadership in the House has been increasingly walled-off. Incumbents tend to serve longer and leadership positions go to the most senior incumbents

- "Internally complex": House functions have been regularized and specialized: committees, leadership, staff.

- Universalistic: The House now follows impersonal, universal decision criteria rather than particularistic criteria. "Precedents and rules are followed; merit systems replace favoritism and nepotism" (p 145) When the House makes a judgment about a contested election, the decision rests on the case's merits, not on partisan lines.

Rules

No comments:

Post a Comment