"All of American history comes from the Civil War. It is the most important event in our history. Everything before it led up to it, everything since, everything, is a consequence of it." -- Ken Burns

From Article I, section 2

Akhil Amar on the Three-Fifths Clause:

The radical vice of Article I as drafted and ratified was that it gave slaveholding regions extra clout in every election as far as the eye could see - a political gift that kept giving. And growing. Unconstrained by any explicit intrastate equality norm in Article I, and emboldened by the federal [3/5] ratio, many slave states in the antebellum era skewed their congressional-district maps in favor of slaveholding regions within the state. Thus the House not only leaned south, but also within coastal slave states bent east, toward tidewater plantations that grabbed more than their fair share of seats. ... The very foundation of the Constitution’s first branch was tilted and rotten.

And not just the first branch. The Article II electoral college sat atop the Article I base: The electors who picked the president would be apportioned according to the number of seats a state had in the House and Senate. In turn, presidents would nominate cabinet heads, Supreme Court justices, and other Article III judges.Consequences of the Three-Fifths Clause. From William Lee Miller, Arguing About Slavery:

Five of the first seven presidents were slaveholders [Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Jackson], for thirty-two of the nation’s first thirty-six years forty of its first forty-eight, fifty of its first sixty four, the nation’s president was a slaveholder. The powerful office of Speaker of the House was held by a slaveholder for twenty-eight of the nation’s first thirty-five years. The president pro tem of the Senate was virtually always a slaveholder. The majority of the cabinet members and — very important — of justices of the Supreme Court were slaveholders. The slaveholding Chief Justice Roger Taney, appointed by slaveholding President Andrew Jackson to succeed the slaveholding John Marshall, would serve all the way through the decades before the war into the years of the Civil War itself; it would be a radical change of the kind slaveholders feared when in 1863, President Lincoln would appoint the anti-slavery politician Salmon P. Chase of Ohio to succeed Taney.

The size of Congress (Davidson 28-29)

The relevant constitutional provision is Article 4, section 3:

New States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new States shall be formed or erected within the jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the CongressThat’s right. All it takes to create a new state is the passage of a federal law. Right now, assuming they were willing to use the nuclear option to abolish the filibuster for state admissions, any unified government could make Puerto Rico or DC a state, or (with the consent of the state leg) divide Texas (or Wyoming) into any number of states. WIth just a law. Irreversibly. And the constitution puts no population or land size constraints on the process either.

These three features of the statehood process—irreversibility, a low threshold for creation, and no population/size constraints on the creation of a state—made the statehood process incredibly destabilzing in the 19th century. Any majority, at any time, could rearrange the balance of power in the legislature and the electoral college. And it unambiguoulsy exacerbated the slave crisis: so manty of the major flashpoints over slavery between 1820 and 1860 involved the flawed statehood process: the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the LeCompton Constitution fight, even the Dred Scot decision.

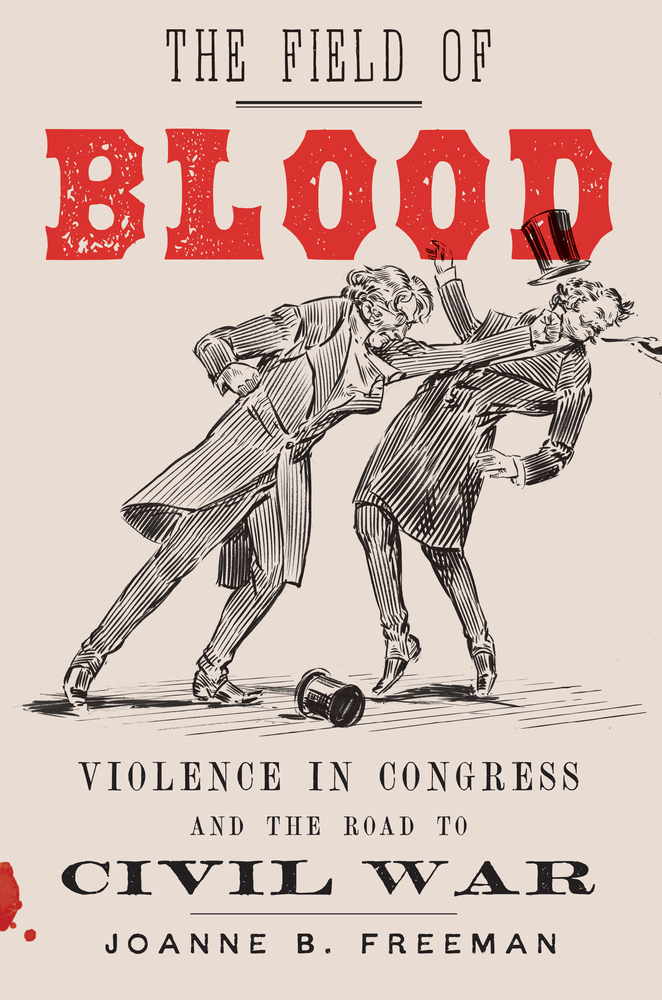

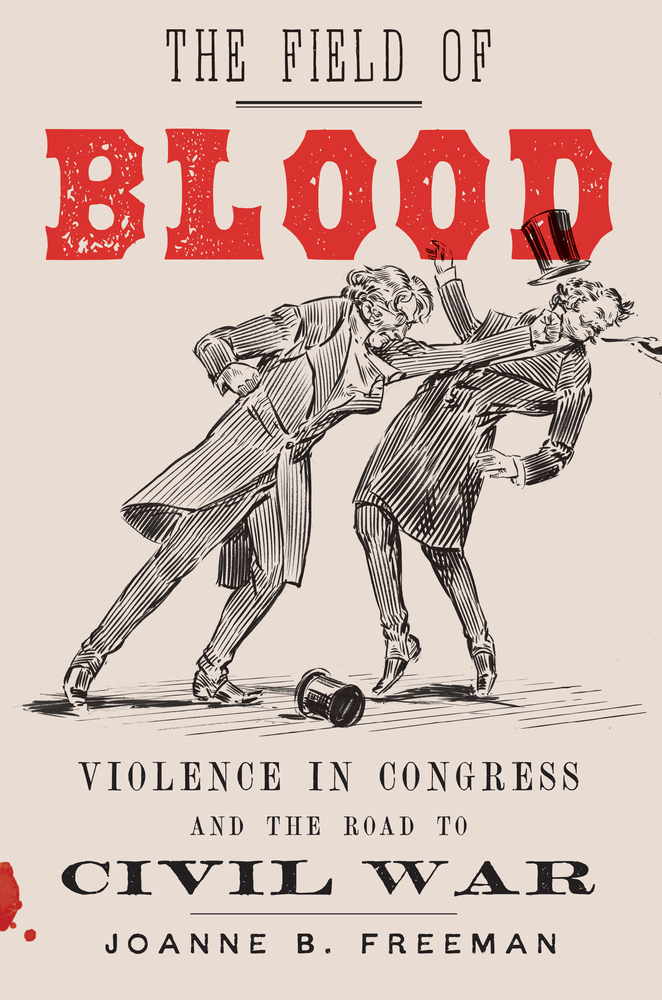

The book on violence in the antebellum Congress:

The title comes from this line, which provides the book's epigraph: In a letter to Senator Charles Sumner (MA) Rev. John Turner Sargent wrote that "blood would flow—somebody’s blood, either yours or Wilson’s, or Hale’s, or Giddings’— before the expiration of your present session on that field of blood, the floor of Congress.”

Sargent was alluding to the burial place of Judas: "And the chief priests took the silver pieces, and said, It is not lawful for to put them into the treasury, because it is the price of blood. And they took counsel, and bought with them the potter's field, to bury strangers in. Wherefore that field was called, The field of blood, unto this day" (Matthew 27:6-8 KJV).

It was literally an atmosphere conducive to violence:

The title comes from this line, which provides the book's epigraph: In a letter to Senator Charles Sumner (MA) Rev. John Turner Sargent wrote that "blood would flow—somebody’s blood, either yours or Wilson’s, or Hale’s, or Giddings’— before the expiration of your present session on that field of blood, the floor of Congress.”

Sargent was alluding to the burial place of Judas: "And the chief priests took the silver pieces, and said, It is not lawful for to put them into the treasury, because it is the price of blood. And they took counsel, and bought with them the potter's field, to bury strangers in. Wherefore that field was called, The field of blood, unto this day" (Matthew 27:6-8 KJV).

It was literally an atmosphere conducive to violence:

All this in a room that was hot, stuffy, and smelly. At the end of a typical day, with the galleries full and hours of body heat trapped in the chamber, French thought that reading aloud to members was like reading “with his head stuck into an oven.” When the House moved to larger windowless quarters in 1857, the acoustics improved but the air didn’t. This wasn’t just a matter of cigar smoke, whiskey fumes, and body odor. A series of climate studies revealed the scope of the problem: no air was circulating in the chamber, and the wisp of a draft that rose through the floor grates had to pass through a layer of “lint, dirt, tobacco quids, expectoration, and filth of every sort.” One member claimed that the “confined and poisonous” air had caused “much sickness and even several deaths,” and indeed, a handful of congressmen died during an average session, though not necessarily because of the air. Ongoing whimpering from the floor produced another study, this one demonstrating that it was thirty degrees warmer inside than outside and that the chamber smelled of sewage from the basement. Visiting the new chamber not long after it opened, French wasn’t impressed. The idea of “shutting up a thousand or two people in a kind of cellar, where none of God’s direct light or air can come in to them . . . does not jump with my notions of living,” he groused. Thirty years later, members still declared the House “the worst ventilated building on the continent."

In 1856, Senator Sumner delivered his famous "Crime Against Kansas" speech. He attacked the absent Andrew Butler (SC), saying he had " a mistress . . . who, though ugly to others, is always lovely to him; though polluted in the sight of the world, is chaste in his sight—I mean," the harlot, Slavery."

Two days later, Butler's cousin, Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina, responded:

You can see the cane in a Boston museum:

Lincoln-Douglas debates

Congress and the Civil War

The congressional oath of office dates from this era.

Shifting partisan composition of Congress:

No comments:

Post a Comment